Strategy and Architecture

As described in the two-chapter hypothetical story on our Home page, AI could contribute to domestic violence remediation with technology that recognizes patterns of abuse before they escalate to critical levels. A well architected, configurable, and highly performing AI platform could serve as an early warning system that connects vulnerable individuals with resources and support networks when they need them the most. Chapter 3, Parts 1, 2, and 3 will lay out the strategy upon which to build the architecture for this complex, sensitive system.

Building a Multi-modal System

This system will need to:

Process natural language across text and voice communications to identify concerning patterns

Employ sentiment analysis to detect emotional escalation

Utilize behavioral pattern recognition to identify deviations from baseline interactions

Create secure information-sharing channels between stakeholders while maintaining privacy

Provide decision support for intervention timing and methodology

Generate customized safety planning based on individual risk profiles

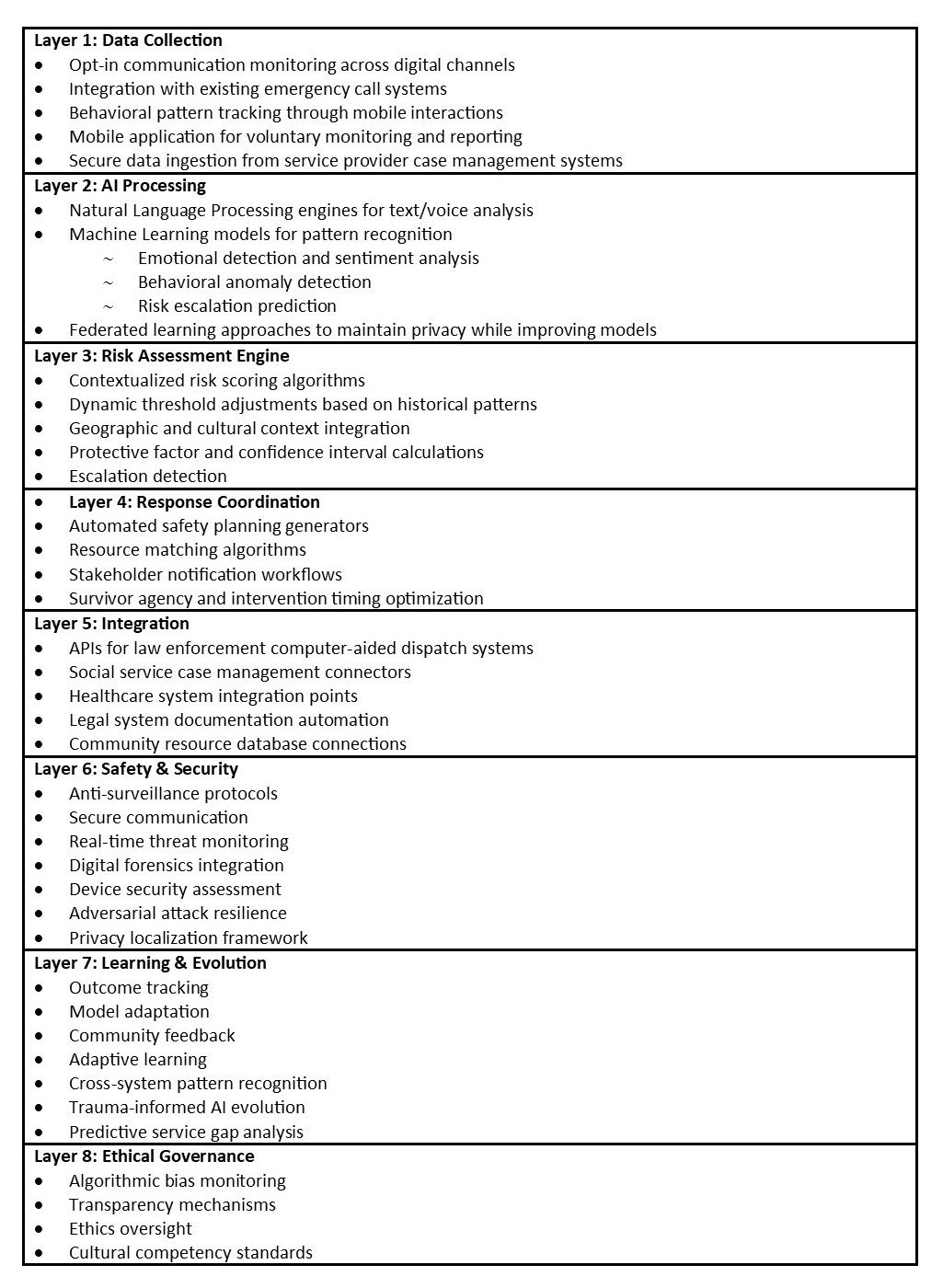

An AI Platform Architecture will require multiple layers. The layered framework offers substantial benefits to interdependent organizations working in this ecosystem. It connects technical implementation to real-world complexity, supporting the understanding of not only the need for architectural separation, but also how these technical decisions directly impact vulnerable populations.

A layered approach creates a "network effect" where each organization's participation increases the value for all other participants while still maintaining appropriate boundaries and controls. The architecture's modularity allows organizations to engage at different levels based on their capacity and needs, making the system more accessible to both large institutions and smaller community-based organizations.

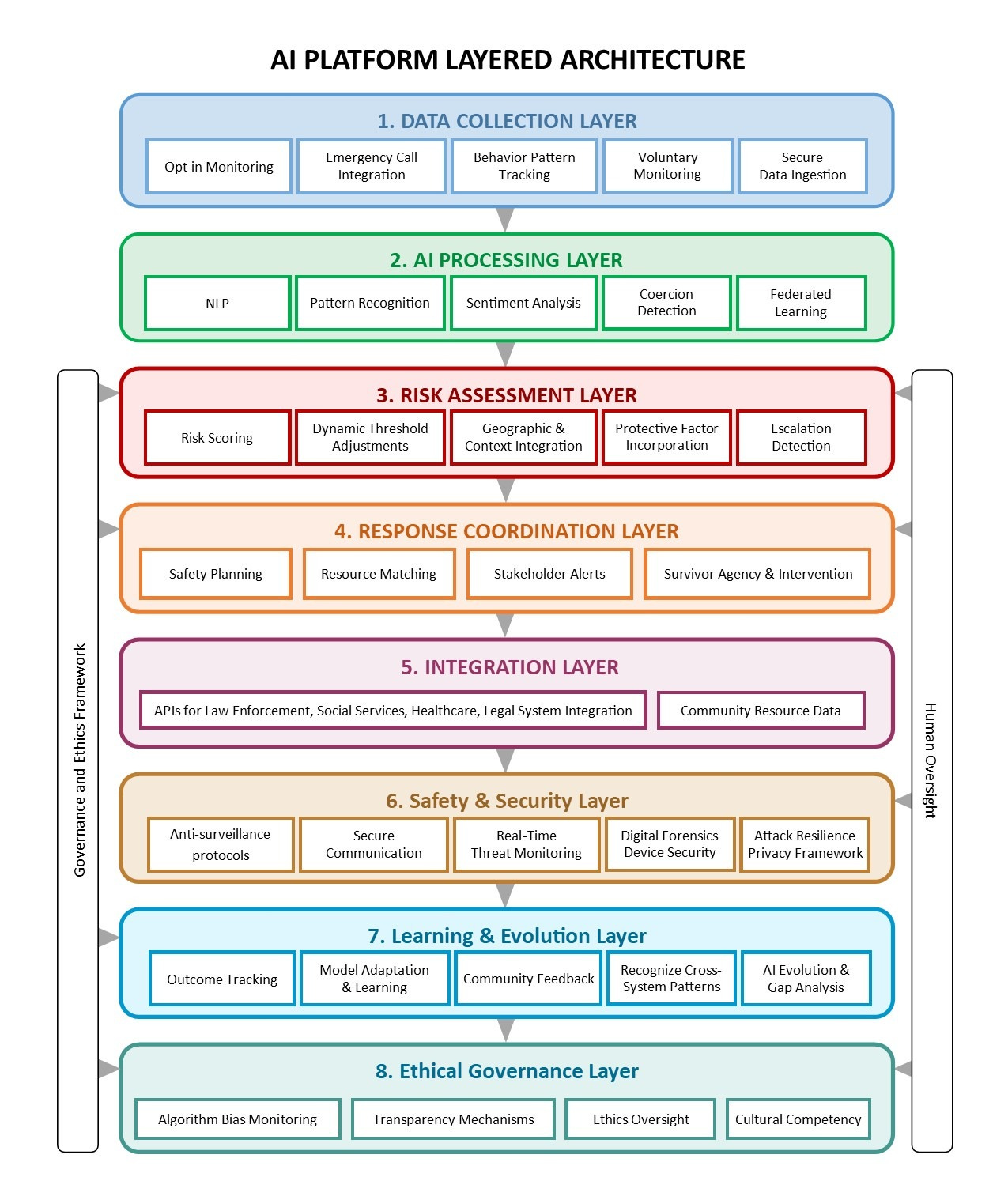

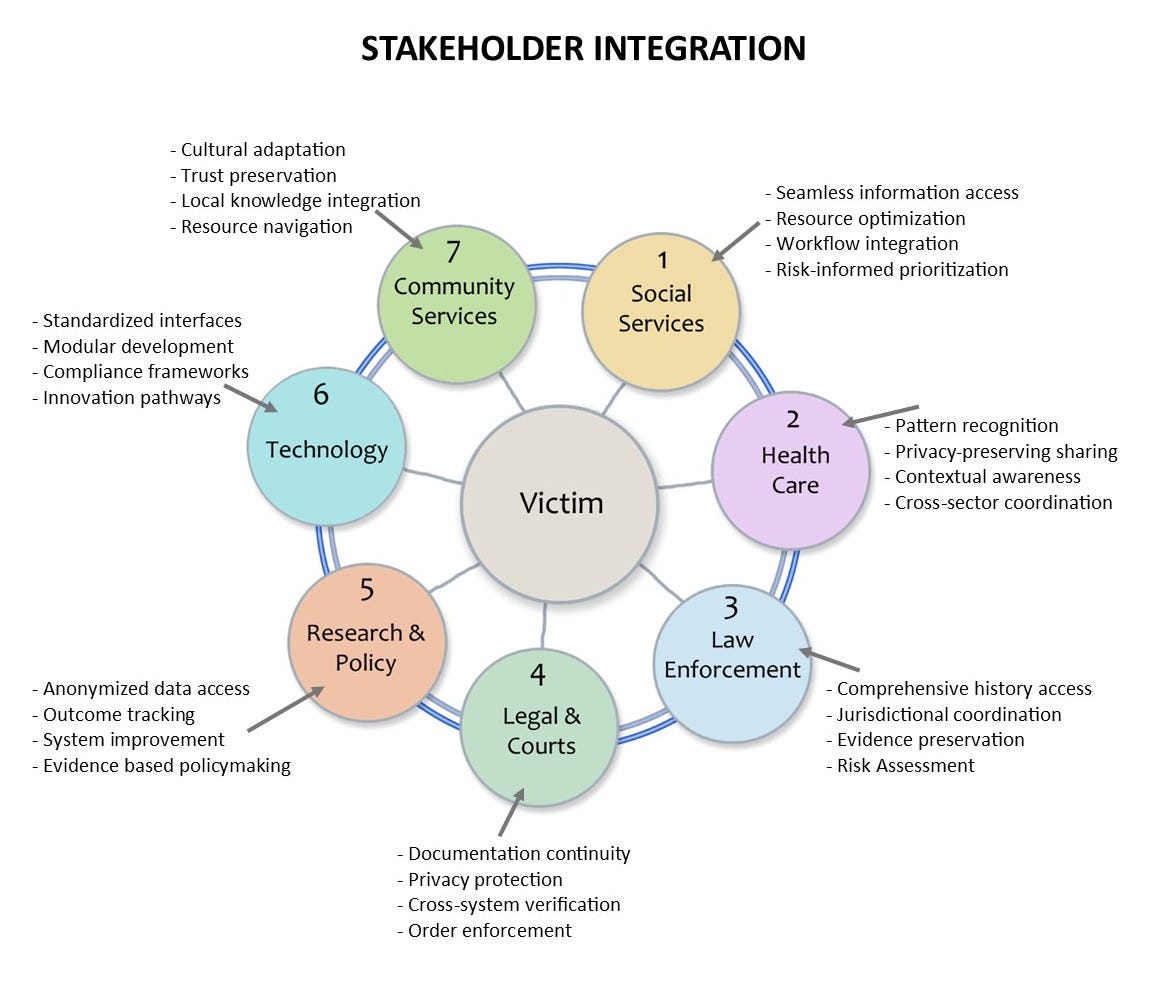

Subset to Layer 5: Integration of Stakeholders

The system must be designed with clear integration points for all relevant stakeholders as described in the following graphic. Optimal stakeholder integration is a direct result of a well-planned, well-architected layered approach. When leveraging AI as a potential domestic violence remediator, each stakeholder group benefits from the cooperation and collaboration of this approach.

Benefits of Layered Framework for Interdependent Stakeholder Organizations

1. For Social Service Providers

Seamless Information Access: Authorized staff can access relevant history without requiring victims to repeatedly recount traumatic events across different agencies

Resource Optimization: The service matching layer helps identify available resources across the network, preventing duplication and addressing gaps

Workflow Integration: The system can integrate with existing case management tools rather than requiring entirely new processes

Risk-Informed Prioritization: Staff can focus on highest-risk cases first while maintaining support for all clients

2. For Healthcare Systems

Pattern Recognition: The analysis layer can identify subtle injury patterns that might not be apparent within a single healthcare encounter

Privacy-Preserving Sharing: The privacy layer enables sharing critical safety information without compromising medical confidentiality

Contextual Awareness: Providers gain appropriate context for injuries without requiring victims to disclose abuse status repeatedly

Cross-Sector Coordination: Healthcare interventions can be aligned with housing, legal, and other concurrent services

3. For Law Enforcement

Comprehensive History Access: Officers responding to incidents can access relevant history through secure, role-based access controls

Jurisdictional Coordination: The integration layer enables information sharing across different jurisdictional boundaries where legally permitted

Evidence Preservation: The data integrity layer ensures information maintains evidentiary standards while protecting privacy

Risk Assessment: Officers gain access to more comprehensive risk factors beyond the immediate incident

4. For Legal and Court System

Documentation Continuity: Judges and attorneys can access consistent historical records across multiple interventions

Privacy Protection: Sensitive details remain protected while providing necessary information for legal proceedings

Cross-System Verification: Information from multiple sources can corroborate patterns within legal standards

Order Enforcement: Protection orders and conditions can be consistently tracked across agencies

5. For Research and Policy Organizations

Anonymized Data Access: The privacy layer enables valuable research without compromising individual identities

Outcome Tracking: The analytics layer supports longitudinal outcome assessment across multiple interventions

System Improvement: Feedback loops identify intervention effectiveness across organizational boundaries

Evidence Based Policymaking: Aggregate data supports policy development grounded in comprehensive outcomes

6. For Technology Partners

Standardized Interfaces: Clear API layers enable integration without requiring access to sensitive underlying data

Modular Development: Partners can focus on specific technical components without rebuilding the entire system

Compliance Frameworks: Security and privacy layers provide clear requirements for technical implementations

Innovation Pathways: The layered architecture allows for component upgrades without systemic disruption

7. For Community-Based Organizations

Cultural Adaptation: The presentation layer can be customized for different communities and languages

Trust Preservation: Strong privacy controls support work with marginalized communities with historical distrust

Local Knowledge Integration: The domain knowledge layer can incorporate community-specific risk factors

Resource Navigation: Smaller organizations gain visibility into the broader service ecosystem

System-Wide Benefits

Reduced Redundancy: Organizations avoid duplicating data collection and management systems

Strengthened Collaboration: Technical connections reinforce organizational relationships

Shared Standards: Common data definitions and quality standards improve cross-system communication

Collective Learning: Insights gained in one part of the system benefit all connected organizations

Resilience: The system maintains functionality even when individual organizations face resource constraints

Consider the Cultural and Societal Elements

Impact of Societal Norms

The effectiveness of any AI system in addressing domestic violence will be significantly influenced by existing cultural and societal factors.

§ Cultural Definitions of Abuse

• Cultural variations in defining abuse and acceptable intervention

• Gender and power dynamics that might impede reporting

• Community-specific norms regarding family privacy

· Religious and traditional frameworks that may impact reporting and intervention

§ Institutional Trust

• Varying levels of trust in law enforcement across communities

• Historical experiences with system responses

• Perceptions of technology as intrusive vs. helpful

• Concerns about surveillance and privacy

§ Gender and Power Dynamics

• Cultural expectations regarding gender roles

• Economic power imbalances that create dependency

• Social pressures against reporting family members

• Community responses to victims who seek help

§ Socioeconomic Factors

• Access to technology

• Economic factors that create dependency barriers

• Housing stability as a factor in reporting abuse

• Resource availability in different communities

An in-depth explanation of these points might be instructive here. Cultural definitions and perceptions of abuse vary significantly across communities, affecting how AI systems recognize, classify, and respond to potential domestic violence. Actions considered abusive in one cultural context may be normalized in another, creating challenges for AI systems trying to identify problematic patterns. Without cultural sensitivity, an AI system might either flag benign cultural practices as concerning (false positives), miss genuine abuse that's culturally normalized (false negatives), or recommend interventions that aren't culturally appropriate.

Examples of these cultural considerations might be:

• Extended Family Dynamics: In many collectivist cultures, extended family members may have significant influence over a couple's decisions. What might appear as third-party control to an AI system trained on Western individualist norms could be normative family involvement in some cultures.

• Financial Management: In some cultures, centralized family financial control is common practice. An AI system might flag one partner managing all finances as financial abuse when it's a mutually accepted arrangement within that cultural context.

• Communication Patterns: Cultures vary in directness of communication. What might read as threatening language in one culture could be normal emphatic expression in another, challenging NLP systems.

• Marriage Expectations: In cultures with arranged marriages or different conceptualizations of marriage as a social/family institution rather than individual choice, the thresholds for what constitutes controlling behavior may differ significantly.

Cultural Variations in Acceptable Intervention

Different cultures have varying expectations about how, when, and by whom domestic issues should be addressed, fundamentally affecting AI system effectiveness. The same intervention approach can be received very differently across cultures, potentially:

· Creating additional harm when interventions violate cultural norms

· Failing to engage victims who don't trust recommended channels

· Missing opportunities to leverage culturally-specific protective factors

Examples:

• Community-Based vs. System-Based Resolution: Some communities prioritize resolution within family or community structures rather than through external systems. An AI system defaulting to law enforcement or court interventions may be rejected in communities with historical distrust of these institutions.

• Gender-Specific Support: In some cultures, female victims may only feel comfortable discussing abuse with other women or may require gender-segregated services, affecting how AI systems should route support.

• Religious Authority: In strongly religious communities, faith leaders may be seen as primary points of intervention. AI systems that don't incorporate these authorities into recommendation pathways may have limited effectiveness.

• Shame and Honor Dynamics: In cultures where family honor is paramount, interventions that create public disclosure may increase risk or be rejected outright. AI systems need to recognize when confidentiality has heightened importance.

• Immigration Consequences: In immigrant communities, fear of deportation or family separation may outweigh other concerns. AI systems need to recognize this when recommending interventions.

Could these factors be addressed in the AI framework? Yes, if these considerations are included:

1. Culturally Diverse Training Data

Systems must be trained on data representing diverse cultural contexts and manifestations of abuse, not just dominant cultural patterns.

2. Cultural Adaptation Layers

The interpretation layer of the AI architecture should include cultural context parameters that adjust risk assessment and intervention recommendations.

3. Community Co-Design

Development must include representatives from diverse communities in the design process, not just as subjects of data collection.

4. Flexible Intervention Pathways

Systems should offer multiple culturally-appropriate intervention options rather than a single pathway.

5. Cultural Competency Metrics

Evaluation frameworks must assess effectiveness across different cultural communities, not just overall performance.

6. Continuous Cultural Learning

Systems need feedback mechanisms to improve cultural understanding over time based on community experiences and outcomes.

7. Cultural Override Options

Human experts with specific cultural knowledge should be able to override system recommendations when cultural nuance is missed.

An Implementation Example

Consider a scenario where an AI system is analyzing communication patterns between partners. In a direct-communication Western context, the statement "You're not going to that event" might be flagged as controlling behavior. However, in a high-context culture where indirect communication is normal, this might be understood differently. A culturally sensitive system would:

1. Consider the cultural background parameters in its analysis

2. Look for additional patterns specific to that cultural context

3. Apply culturally-appropriate thresholds before flagging

4. Recommend culturally-aligned intervention options

5. Present information in culturally resonant language and framing

By incorporating cultural intelligence into the AI architecture, systems can avoid imposing one cultural standard across diverse communities while still effectively identifying and addressing domestic violence in its various manifestations.

Culturally-Adaptive Interfaces:

Language customization beyond simple translation

Culturally appropriate visual design

Interaction patterns that respect cultural norms

Content that reflects diverse lived experiences

Variable Threshold Adjustment:

Community-specific baseline calibration

Cultural context integration in risk assessment

Recognition of culturally-specific risk factors

Adaptation to different communication styles

Alternative Access Pathways:

Non-technological access points for digital divides

Integration with trusted community organizations

Multiple reporting channels with varying levels of formality

Anonymous options where cultural stigma exists

Trust-Building Features:

Transparency in data usage and decision-making

Clear opt-in/opt-out controls

Community oversight integration

Evidence of effectiveness shared appropriately

So, what is appropriate? In this particular AI use case, the word needs some clarification. Appropriate sharing of evidence of effectiveness requires finding the right balance between necessary transparency for accountability, validation, and improvement, as well as essential protection of survivor privacy, safety, and dignity. This balance varies significantly based on audience, content, method, and context.

Audience-Specific Appropriateness:

For Survivors and Potential Users

Appropriate:

Clear, non-technical explanations of how the system helps without overpromising

Concrete examples of system limitations and safeguards

Honest risk-benefit analyses in accessible language

Testimonials that preserve anonymity while conveying authentic experiences

Inappropriate:

Sharing identifiable stories without explicit consent

Technical details that could enable system manipulation by abusers

Marketing claims unsupported by evidence

Oversimplifications that create false security

For Practitioners and Service Providers

Appropriate:

Detailed performance metrics relevant to their specific role

Case-based learning scenarios (properly anonymized)

Comparative effectiveness against current approaches

Integration requirements and limitations

Cultural and contextual variation in effectiveness

Inappropriate:

Raw data that could compromise confidentiality

Metrics that encourage inappropriate profiling

Effectiveness claims that ignore practitioner expertise

For Researchers and System Developers

Appropriate:

Methodologically sound evaluation frameworks

Properly anonymized datasets with informed consent

Detailed analysis of system failures and edge cases

Disaggregated performance across different populations

Clear documentation of limitations and biases

Inappropriate:

Unnecessarily detailed personal narratives

Data sharing beyond research purposes

Evidence that reinforces harmful stereotypes

Metrics that prioritize technical performance over human impact

For Funders and Policymakers

Appropriate:

Population-level impact measurements

Cost-effectiveness and resource utilization metrics

Comparative analysis against policy alternatives

Long-term outcome tracking beyond immediate usage

Ethical and implementation challenges

Inappropriate:

Simplified metrics that obscure nuance

Success measures disconnected from survivor experiences

Data that could jeopardize program funding based on misunderstood metrics

Content-Specific Appropriateness

Quantitative Evidence

Appropriate:

Risk assessment accuracy rates with confidence intervals

Intervention uptake rates and completion statistics

Safety outcome measurements with appropriate timeframes

Disaggregated performance across demographics

System utilization patterns

Inappropriate:

Metrics that create perverse incentives

Statistics without contextual factors

Correlations presented as causation

Performance metrics that oversimplify complex situations

Qualitative Evidence

Appropriate:

Thematic analysis of user experiences

Practitioner feedback on system integration

Analysis of unexpected outcomes or uses

Cultural response variations

Narrative insights that illuminate quantitative findings

Inappropriate:

Individual stories that risk identification

Emotional testimonials without substantiation

Selective positive feedback without balanced critique

Method-Specific Appropriateness

Appropriate Evidence Collection Methods:

Trauma-informed research protocols

Ongoing consent processes (not just initial consent)

Multiple feedback channels (both direct and anonymous)

Participatory evaluation involving survivors

Independent third-party assessment

Long-term outcome tracking beyond immediate usage

Inappropriate Evidence Collection Methods:

Unnecessarily intrusive data collection

Research designs that create safety risks

Evaluations focused solely on system usage without outcome measurement

Methods that privilege certain voices (e.g., English-speaking, tech-savvy)

Assessment approaches disconnected from lived experiences

Context-Specific Appropriateness

Timing Considerations:

Evidence sharing during acute crisis may differ from non-crisis contexts

Pilot phase evidence requires different framing than established program evidence

Historical context of previous intervention failures must be acknowledged

Cultural Considerations:

Evidence must acknowledge cultural variation in both problem definition and intervention effectiveness

Different communities may require different evidence formats and sources

Culturally-specific success metrics may be more relevant than universal standards

Power Dynamics:

Evidence sharing should avoid reinforcing existing power imbalances

Multiple knowledge sources (including experiential knowledge) should be valued

Evidence should support survivor agency, not system control

Implementation of Appropriate Sharing

To implement appropriate evidence sharing:

Create tiered access frameworks - Different stakeholders receive different levels of detail

Develop clear consent protocols - Especially for case examples and testimonials

Establish ethical review processes - For all evidence collection and sharing

Design specific documentation - Tailored to different audience needs

Build feedback mechanisms - To refine what appropriate means over time

Involve community oversight - In determining sharing standards and practices

Consideration of these dimensions can govern evidence that advances system improvement and accountability while respecting the profound sensitivity of domestic violence contexts and prioritizing survivor wellbeing.